Relationships

How I think about ’em…

Why are relationships such hard work? Shouldn't this be a lot easier if we both love each other and are decent people?

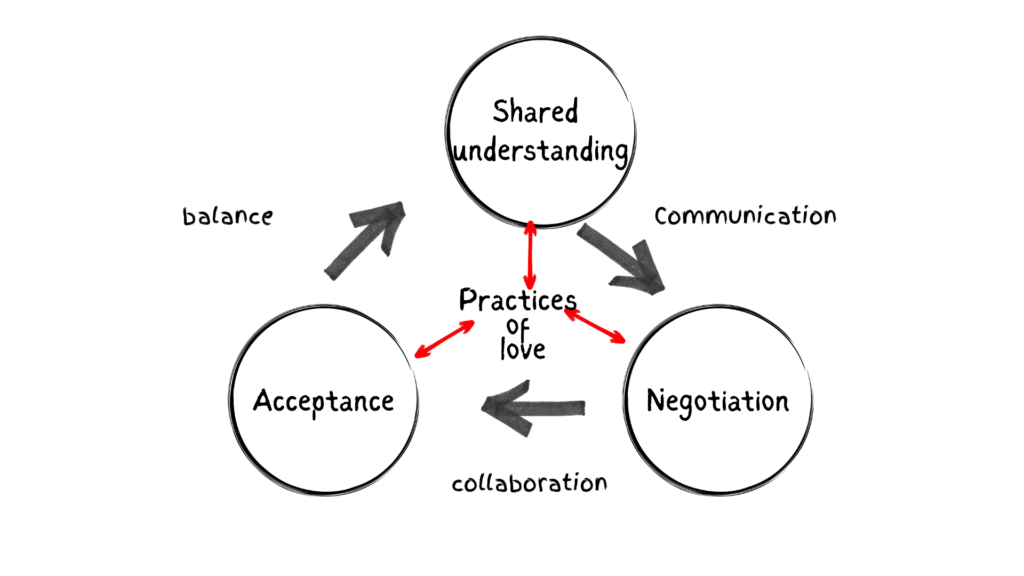

Practices of love

Relationships don’t have to be “hard work,” per se, but they are work. By that I mean, the specific practices that support your relationship must be done consciously, intentionally, and continually. And no, just because you’re both good people and love one another, it’s not supposed to be easy. Here’s why: most of us don’t learn how to be good partners when we’re kids. We learn to be good people, yes. Being a good partner is not the same as being a good person. And the feelings of love do not keep people together. The practices of love keep people together. What exactly are practices of love? They are specific commitments to actions that support your loving relationship, and they are unique to each couple. Figuring out what those practices are is one of the things we do together in therapy.

Poets don’t craft poems about the practices of love, novelists don’t write books about the practices of love, filmmakers don’t make movies about the practices of love. So we all grow up believing that if we feel love for the other person, it should all work out. And not just work out — it should be easy. But human relationships are extremely complicated. Can you think of one other extremely complicated human endeavor that does not take regular practice, or that you can do just because it “feels” like you should be able to do it? Would you walk into the cockpit of a 747 mid-flight and say, “Hey folks — whaddaya say I land this thing? Feels like I oughtta be able to do this.” Or an operating room? “Gang, I have a kidney, I know where they are — how about I take this one out? Feels like something I should be able to do.” But that’s exactly what we do when it comes to human relationships, and human relationships are infinitely more complicated than landing a Boeing or performing surgery.

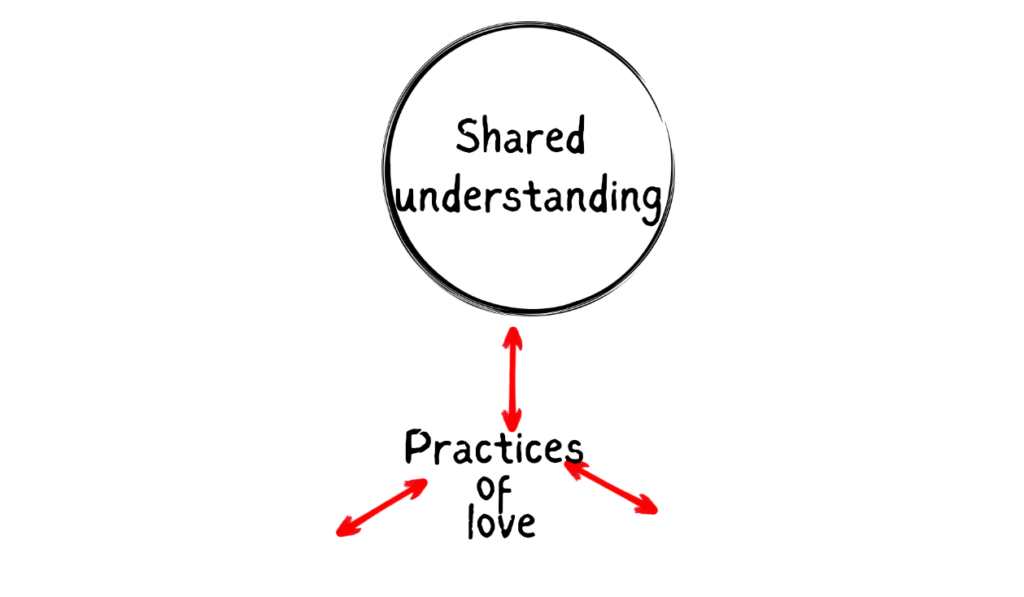

It starts with a shared story

Okay, you’ve got your practices of love, and your feelings of love, but you keep having the same arguments or conflicts over and over. One of the reasons this happens is because there are certain conversations you can’t have until you know how to have them. Learning how to have to have more meaningful and resolvable conversations begins with shared stories, or a shared understanding of the problem.

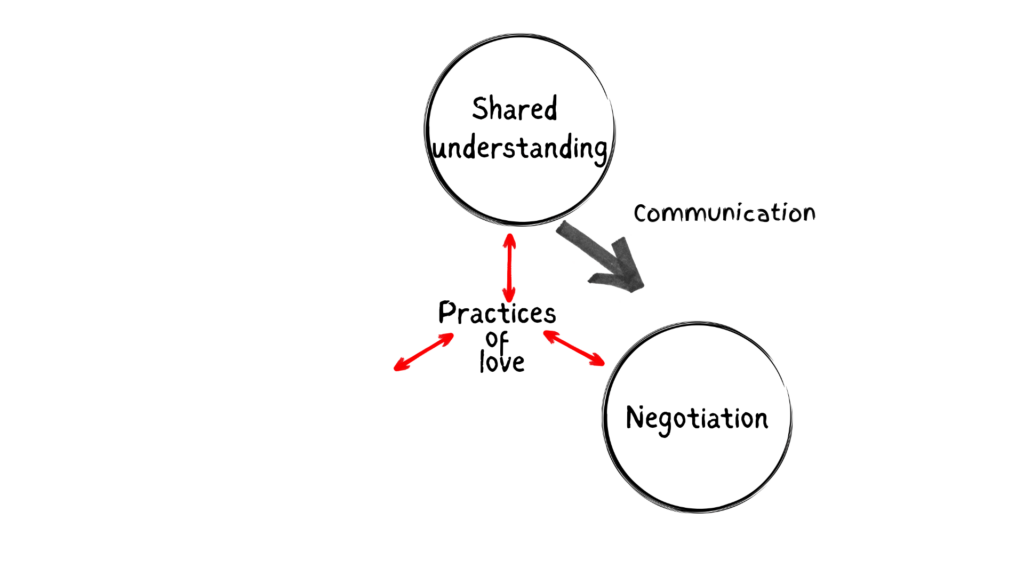

We all have our own subjective experiences, and we all tend to make up stories about what our partners are experiencing (we think we know what they’re feeling or going through), but until we take the time to really, truly ask what it’s like to be them in any given context, those stories remain just that — stories. They are stories that could be true, but they are still stories. What we aim for are shared stories, a rich understanding by both partners of the other’s experience. How you arrive at a shared understanding — the communication tools — is also what we work on in therapy. Once we have that shared understanding, we can begin to navigate those experiences and arrive at a resolution — that often requires some kind of negotiation.

Negotiation is not a dirty word

If you have the communication tools to arrive at a shared story, you have the tools to negotiate a resolution. Yes, negotiate. It’s not a bad word. You and your partner are probably already doing it in a hundred small ways. Resolution is the process of arriving at a shared understanding and negotiating what happens in that given context. More often than not when I ask a couple, “What did you negotiate about this?” the answer is “nothing.” Couples may talk about a problem (while not arriving at a shared understanding), but often don’t take the next step — which is asking what does the relationship need from us right now?

Your relationship is its own ecosystem. You and your partner have needs, of course, but the relationship has its own needs. There are super-needs (needs that always exist, regardless of context, and are based your practices of love), and contextual needs (specific needs determined by a given set of circumstances). One of the things we work on in therapy is getting better at determining the relationship’s needs.

The opposite of resentment is acceptance

After you have a shared understanding of one another’s experiences, and you’ve negotiated the resolution, comes acceptance. Acceptance is completely different from concession. Resentment comes from concession — when one of you just waves a white flag and gives up arguing your position. Acceptance means you understand what your partner’s experience is, what the relationship needs most right now, and you have agreed upon a next step. One of you may not like the outcome — you may have preferred something different — but you can accept the outcome in support of the relationship, without resentment.

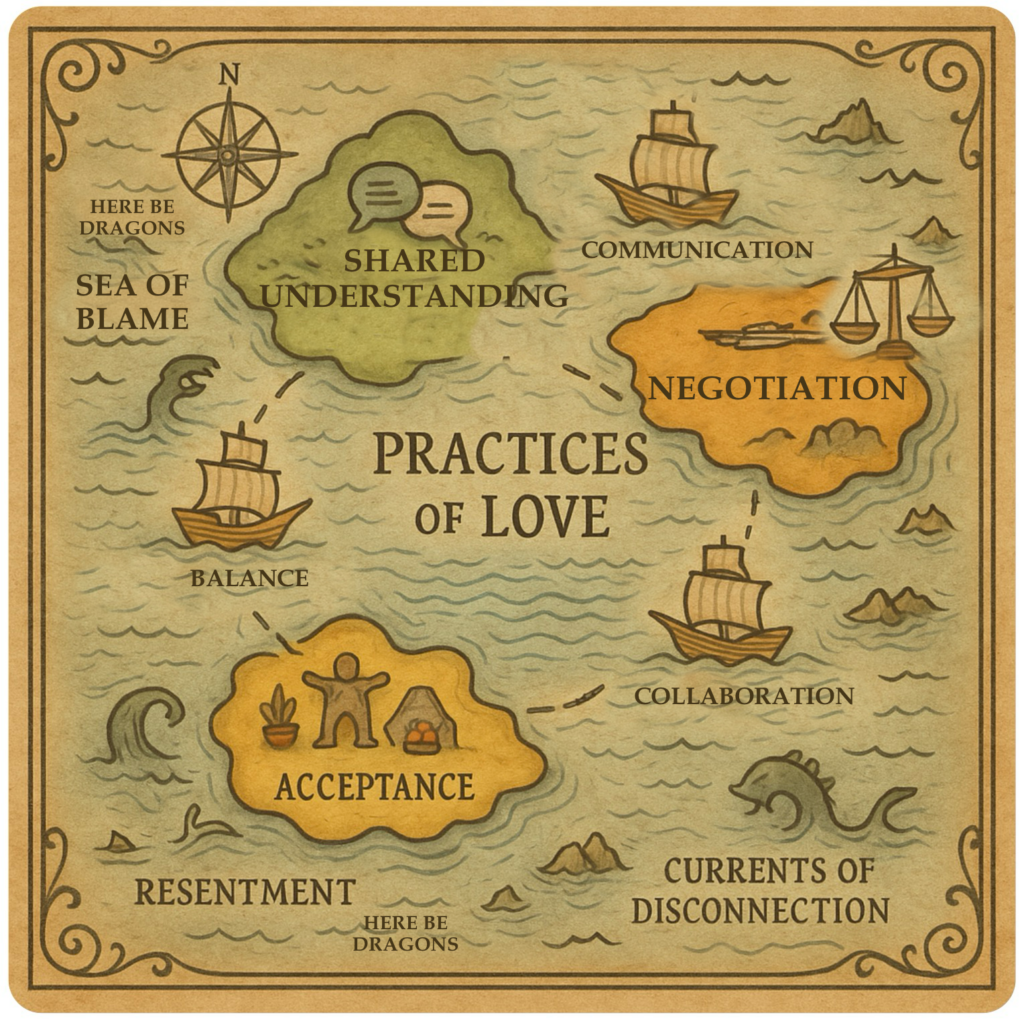

Putting it all together with metaphor

I love metaphors (and use them regularly in sessions) — they use familiar objects or ideas to help explain concepts that might initially be difficult to understand.

You can think of the Practices of Love as a safe harbor, surrounded by three islands: Shared Understanding, Negotiation, and Acceptance. To get from Shared Understanding to Negotiation you must set sail on sturdy vessel of Communication; to get from Negotiation to Acceptance, you must navigate the vessel Collaboration; and to be willing to make the trip from Acceptance back to Shared Understanding will require the ship of Balance, ensuring that each partner steers the relationship toward resolutions with equity. Veering off course risks Disconnection, Resentment, and Blame.

Half of the time we're gone

But we don't know where

Paul Simon, The Only Living Boy In New York